2012: Archaeology and Hollywood

Part Five of Five - Mass Entertainment and The End

November 21, 2009

In the prior chapters of this CyArk blog series, we have talked about the idea of the year 2012: What it means to modern people, and what it may have meant to the Classic Period Maya of Central America. The Maya are a still-living people whose Long Count calendar (used between approximately 30 BCE and 900 AD/CE) forms the main basis for the current hysteria which links 2012 to a possible, world-changing event of a transformative or destructive nature. These episodes are as follows: Introduction, Millenarianism (apocalyptic thought), New Age Predictions, The Maya People, The Maya Calendars, and Maya Predictions. Now, it is time for the elephant in the room: The feature film 2012 and all of its accompanying mass media spectacles, countless newspaper and magazine articles, blogs (including this one), and TV presentations. All of these feed the flames of public curiosity, hype, and a certain measure of hysteria about what has become a cultural phenomenon, one not dissimilar to the Y2k scare a decade ago but with the exotic, foreign twist implicit to discussions of ancient belief systems from cultures other than our own.

The highest profile manifestation of this particular cultural phenomenon is a new feature film titled, simply, 2012. Its plot is partially based on data from the results of archaeological research, specifically breakthroughs in reading Classic Period Maya glyphic writing. These breakthroughs have given us great insight into their calendars, history, and beliefs. That this archaeological knowledge would undergo creative adaptation into entertainment should come as no surprise. Even if we don't count the incredibly popular Indiana Jones series of films, Hollywood has for many decades had a relationship with the romantic aspects and sensational discoveries of the occasionally-stuffy academic discipline of archaeology. These films always combine a public fascination with the new (old), and how it resonates with us and our own perspectives; this resonance with the audience is a particularly vital element if a film is to find a wide viewership.

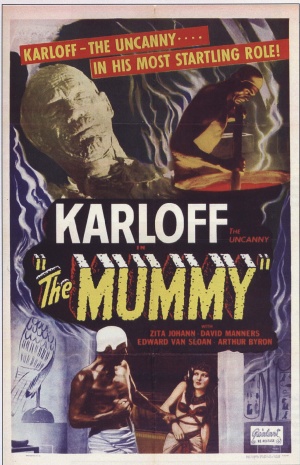

Of course, the specific topics of films that incorporate aspects of knowledge produced from archaeology (sometimes called the archaeological narrative) have changed over time as new discoveries are made. In the early years of film, Egyptology (particularly mummification) was a very hot topic as major discoveries were still being made in the Valley of the Kings. Though archaeological excavation of the largely-undisturbed tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922 offered inspiration for the 1932 Boris Karloff film The Mummy (re-made in 1999), it was not the first offering by Hollywood on this subject. A 1911 film also titled The Mummy was presented as a comedy, wherein a young Egyptologist accidentally electrifies a female mummy back to life (a la Frankenstein) who promptly falls for him, much to the chagrin of his fiancee. A more reflective take on the physical remains of Egypt's famed past was created by the Egyptian writer/director Chadi Abdel Salam, whose 1973 film al-Mummia depicts the discovery of a large cache of Royal Mummies at Luxor by a poor, 19th-century Egyptian family that makes a living by looting ancient sites; the family's need for subsistence conflicts with guilt over the exploitation of their country's heritage.

Egyptology is far from the only archaeological subfield interpreted by Hollywood, however. Paleoanthropology is the archaeological and biological study of early human development and prehistoric culture. The field strives to understand how the earliest people lived and what they looked like. Though cavemen had been depicted in films as far back as Buster Keaton's comedy Three Ages (1923), paleoanthropology became a common subject for feature films in the 1960s-1970s, when major advances in excavation and fossil/lithic (stone) analysis were accompanied by the discovery of early hominids such as Lucy and Lake Turkana Boy (Lewin 120). As with Egyptology, a wide range of paleoanthropology-themed films, from silly comedies to serious dramas, explored newly-formed ideas about the lives of prehistoric humans. While sex symbol Raquel Welch starred in One Million Years B.C. (1967) wearing a fur bikini and Fred Flintstone used his own feet to power a stone-age car on The Flintstones (1960-1966), the Stanley Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) featured an introductory sequence that portrays early humans in a more Paleoanthropologically-informed manner - as animals evolving into a higher consciousness.

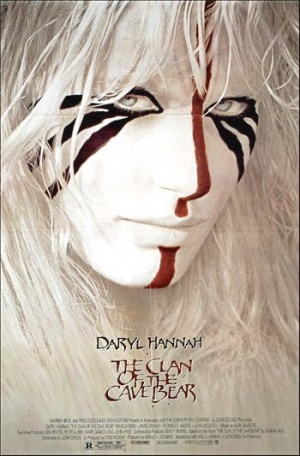

This more-serious evolutionary approach was further explored in the 1980s with the release of films such as Quest For Fire and Clan of the Cave Bear that dramatize the lives of our early ancestors, though the characters in these films occasionally display unquestionably modern behaviors that provide for a bit of unintentional comedy. This brand of unintentional prehistoric silliness was displayed most prominently (and recently) in 2012-director Roland Emmerich's 10,000 B.C. (2008); a fast-paced stone age adventure/drama in which noble Mammoth-hunting savages (speaking full English) must fight giant dinosaur-like birds, sabre-toothed tigers, and a slave-hunting new civilization in the desert that is building massive Egyptian-style pyramids using Wooly Mammoths as labor. An implausible scenario, to put it mildly, but one that entertains nonetheless.

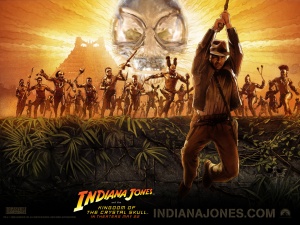

Now, in the first decade of the 21st century, the narratives of Mayanist archaeology have become the subject of several feature films. Mel Gibson's highly-controversial epic Apocalypto (2006) attempted to dramatize the lives of Maya people during the so-called Maya Collapse around 900 CE. In an ambitious effort at archaeoogical-correctness, the filmmakers meticulously studied Classic Period Maya artwork to replicate styles of dress and even used the Yucatec Maya language for its dialogue, the first time a feature film was made in this language. The final film, however, was heavily criticized by archaeologists for a wide range of perceived inaccuracies. These included depictions of human sacrificial practices that were Aztec, not Maya, as well as historical inaccuracy in conflating the time frame of the Maya Collapse with that of the Spanish Conquest (for two excellent archaeological critiques by Mayanists on Apocalypto, go to Gerardo Aldana's article and Zachary X. Hruby's article). More light-heartedly, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) embellished Steven Spielberg's long-running Indiana Jones franchise with strongly Maya-themed pyramids, paintings, glyphic inscriptions, and language-references; this was despite the fact that the film was set mostly in the Amazon of South America, not in the Central American home of the Maya (past and present). In keeping with the fantastical nature of the Indiana Jones enterprise and in a direct homage to Chariots of the Gods? author Erich Von Daniken, it turns out Spielberg's ancient Maya were aliens all along, waiting for the right moment to turn their pyramids back into spaceships and zoom off into the cosmos.

In every single one of these films, the stories have been carefully crafted to address the dreams, concerns, and sense of humor of the modern-day audiences that view them. Simultaneously serving as art (however bad) and entertainment, all of these films use some version of archaeological narrative as an initial jumping-off point for a director and writer's onscreen vision that resonates both with them and the audience. This task necessitates taking frequent liberties with the narratives of archaeologists, whose methodical and evidence-based approaches don't often make for a fast-moving story with unambiguous conclusions. As a result, the path from field research to feature film can thus result in a peculiar archaeological version of the Game of Telephone: First, field archaeologists publish their findings and speculations in journals and scholarly books, which are then presented in a slightly-altered (simplified) version in popular science media such as National Geographic, Archaeology Magazine, and CyArk. Both the scholarly books and popular science media are then used as sources for books and other media outside of academic circles, such as those by New Age spiritualists; these present a more heavily-altered version of the original narrative, replete with new conclusions and speculations. Then, all of these sources trickle down and combine in the echo chamber of the internet, that vast storehouse of information which allows the individual to prove or disprove anything he or she desires - assuming this individual ignores the question of how valid their sources are. After picking up steam on the internet and the other aforementioned popularizing media, the greatly-altered narrative bursts into mass consciousness on television and film. The ubiquitousness of TV and movies act in turn like steroids on the internet echo chamber, where growing numbers of newly-minted "experts" endlessly debate different aspects of fact and fiction pertaining to a story that often retains only the most superficial resemblance to the archaeological narrative it was originally drawn from. The producers of television and film spectaculars, however, are far more concerned with how their final product resonates with (sells to) a mass audience than they are with any questions as to how realistic or plausible their storyline is - or what version of a particular narrative it is drawn from.

This concern with audience resonance (ticket sales) defines the final cut of the film 2012 itself - Chock-full of spectacular special effects and clocking in at two and a half hours, the film's editors seem to have cut a majority of the backstory that is heavily alluded-to on the film's promotional website. This website, which includes details on decades of preparation by the fictional IHC (Institute for Human Continuity) for the End Of The World, is far more influenced by millenarianist and New Age spiritualist ideas about 2012 than the archaeological narrative source material by Mayanist scholars. Regardless, very few of these details appear in the final film, which only refers a couple of times to the Maya calendars and their purported predictions of a "Galactic Alignment" (clearly modeled after John Major Jenkins' ideas in Maya Cosmosis 2012) that brings about the end of the world. Indeed, the main proponent of these ideas in the film is the character Charlie Frost, entertainingly portrayed as a burned-out hippie [millenarianist] by legendary loose-cannon actor Woody Harrelson; a character that reviewer Manohla Dargis, writing in the New York Times, humorously suggested might be modeled after New Age psychedelic journeyman Daniel Pinchbeck, author of 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl. Harrelson's fringe element turns out to be correct in the film, of course, but the intent seems at least as comedic as it is contemplative. In fact, the film's portrayal of The End of The World presents itself as almost an apocalyptic version of slapstick, in which seemingly-indestructible, wisecracking lead actor John Cusack speeds his family to safety in a series of high-speed vehicles as the earth's crust collapses in their wake.

2012 is relentlessly entertaining, a little exhausting at 2.5 hours in length, and utterly ridiculous. It plays shamelessly to our anxieties and intense curiosity about total apocalypse, a subject people have been fascinated by across countless cultures and vast spans of time. The film has practically nothing to do with the Maya calendar, which is relegated to a footnote in this piece of Hollywood showmanship. In this, the film 2012 is similar to and perhaps even more honest than other mass entertainment spectacles which involve stories and data adapted from archaeological narratives - it aims to be pure entertainment, and little more, feeding, exciting, and echoing our modern desires and fears while the year/date itself and its exotic origins serve as simple window dressing to a story about us - well, the Hollywood version of us, anyway.

More worrisome than the film itself is public hysteria around the actual date of December 21 (or 23), 2012, which has generated a great deal of fear and, for some people who are a bit more emotionally fragile, threats of suicide (see this article from National Geographic for more examples and information). This hysteria has been fed by the makers of the film for the purpose of hyping it, and it is growing increasingly difficult (particularly on the internet) to find voices of reason in an often-sinister wilderness of open speculation on the subject.

Hopefully, this hysteria will subside as calmer heads prevail and make their voices heard. Though we have a more-than-excellent chance of waking up on December 22 (or 24), 2012, in the same shape as we were when we went to sleep, we might want to keep an eye on those of us who are a bit more impressionable than others. Take a moment to let these worriers know they should take all the scary things they are reading on the internet about 2012 with a grain of salt - or twenty. After all, the ancient Maya didn't seem concerned enough to really write much of anything about it. Should we?

References:

Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams

Lewin, Roger (2005). Human evolution: an illustrated introduction. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell

The highest profile manifestation of this particular cultural phenomenon is a new feature film titled, simply, 2012. Its plot is partially based on data from the results of archaeological research, specifically breakthroughs in reading Classic Period Maya glyphic writing. These breakthroughs have given us great insight into their calendars, history, and beliefs. That this archaeological knowledge would undergo creative adaptation into entertainment should come as no surprise. Even if we don't count the incredibly popular Indiana Jones series of films, Hollywood has for many decades had a relationship with the romantic aspects and sensational discoveries of the occasionally-stuffy academic discipline of archaeology. These films always combine a public fascination with the new (old), and how it resonates with us and our own perspectives; this resonance with the audience is a particularly vital element if a film is to find a wide viewership.

Egyptology in Film

Of course, the specific topics of films that incorporate aspects of knowledge produced from archaeology (sometimes called the archaeological narrative) have changed over time as new discoveries are made. In the early years of film, Egyptology (particularly mummification) was a very hot topic as major discoveries were still being made in the Valley of the Kings. Though archaeological excavation of the largely-undisturbed tomb of King Tutankhamun in 1922 offered inspiration for the 1932 Boris Karloff film The Mummy (re-made in 1999), it was not the first offering by Hollywood on this subject. A 1911 film also titled The Mummy was presented as a comedy, wherein a young Egyptologist accidentally electrifies a female mummy back to life (a la Frankenstein) who promptly falls for him, much to the chagrin of his fiancee. A more reflective take on the physical remains of Egypt's famed past was created by the Egyptian writer/director Chadi Abdel Salam, whose 1973 film al-Mummia depicts the discovery of a large cache of Royal Mummies at Luxor by a poor, 19th-century Egyptian family that makes a living by looting ancient sites; the family's need for subsistence conflicts with guilt over the exploitation of their country's heritage.

Paleoanthropology in Film

Egyptology is far from the only archaeological subfield interpreted by Hollywood, however. Paleoanthropology is the archaeological and biological study of early human development and prehistoric culture. The field strives to understand how the earliest people lived and what they looked like. Though cavemen had been depicted in films as far back as Buster Keaton's comedy Three Ages (1923), paleoanthropology became a common subject for feature films in the 1960s-1970s, when major advances in excavation and fossil/lithic (stone) analysis were accompanied by the discovery of early hominids such as Lucy and Lake Turkana Boy (Lewin 120). As with Egyptology, a wide range of paleoanthropology-themed films, from silly comedies to serious dramas, explored newly-formed ideas about the lives of prehistoric humans. While sex symbol Raquel Welch starred in One Million Years B.C. (1967) wearing a fur bikini and Fred Flintstone used his own feet to power a stone-age car on The Flintstones (1960-1966), the Stanley Kubrick film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) featured an introductory sequence that portrays early humans in a more Paleoanthropologically-informed manner - as animals evolving into a higher consciousness.

This more-serious evolutionary approach was further explored in the 1980s with the release of films such as Quest For Fire and Clan of the Cave Bear that dramatize the lives of our early ancestors, though the characters in these films occasionally display unquestionably modern behaviors that provide for a bit of unintentional comedy. This brand of unintentional prehistoric silliness was displayed most prominently (and recently) in 2012-director Roland Emmerich's 10,000 B.C. (2008); a fast-paced stone age adventure/drama in which noble Mammoth-hunting savages (speaking full English) must fight giant dinosaur-like birds, sabre-toothed tigers, and a slave-hunting new civilization in the desert that is building massive Egyptian-style pyramids using Wooly Mammoths as labor. An implausible scenario, to put it mildly, but one that entertains nonetheless.

The Ancient Maya in Film

Now, in the first decade of the 21st century, the narratives of Mayanist archaeology have become the subject of several feature films. Mel Gibson's highly-controversial epic Apocalypto (2006) attempted to dramatize the lives of Maya people during the so-called Maya Collapse around 900 CE. In an ambitious effort at archaeoogical-correctness, the filmmakers meticulously studied Classic Period Maya artwork to replicate styles of dress and even used the Yucatec Maya language for its dialogue, the first time a feature film was made in this language. The final film, however, was heavily criticized by archaeologists for a wide range of perceived inaccuracies. These included depictions of human sacrificial practices that were Aztec, not Maya, as well as historical inaccuracy in conflating the time frame of the Maya Collapse with that of the Spanish Conquest (for two excellent archaeological critiques by Mayanists on Apocalypto, go to Gerardo Aldana's article and Zachary X. Hruby's article). More light-heartedly, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) embellished Steven Spielberg's long-running Indiana Jones franchise with strongly Maya-themed pyramids, paintings, glyphic inscriptions, and language-references; this was despite the fact that the film was set mostly in the Amazon of South America, not in the Central American home of the Maya (past and present). In keeping with the fantastical nature of the Indiana Jones enterprise and in a direct homage to Chariots of the Gods? author Erich Von Daniken, it turns out Spielberg's ancient Maya were aliens all along, waiting for the right moment to turn their pyramids back into spaceships and zoom off into the cosmos.

Entertainment vs. Archaeological Narrative

In every single one of these films, the stories have been carefully crafted to address the dreams, concerns, and sense of humor of the modern-day audiences that view them. Simultaneously serving as art (however bad) and entertainment, all of these films use some version of archaeological narrative as an initial jumping-off point for a director and writer's onscreen vision that resonates both with them and the audience. This task necessitates taking frequent liberties with the narratives of archaeologists, whose methodical and evidence-based approaches don't often make for a fast-moving story with unambiguous conclusions. As a result, the path from field research to feature film can thus result in a peculiar archaeological version of the Game of Telephone: First, field archaeologists publish their findings and speculations in journals and scholarly books, which are then presented in a slightly-altered (simplified) version in popular science media such as National Geographic, Archaeology Magazine, and CyArk. Both the scholarly books and popular science media are then used as sources for books and other media outside of academic circles, such as those by New Age spiritualists; these present a more heavily-altered version of the original narrative, replete with new conclusions and speculations. Then, all of these sources trickle down and combine in the echo chamber of the internet, that vast storehouse of information which allows the individual to prove or disprove anything he or she desires - assuming this individual ignores the question of how valid their sources are. After picking up steam on the internet and the other aforementioned popularizing media, the greatly-altered narrative bursts into mass consciousness on television and film. The ubiquitousness of TV and movies act in turn like steroids on the internet echo chamber, where growing numbers of newly-minted "experts" endlessly debate different aspects of fact and fiction pertaining to a story that often retains only the most superficial resemblance to the archaeological narrative it was originally drawn from. The producers of television and film spectaculars, however, are far more concerned with how their final product resonates with (sells to) a mass audience than they are with any questions as to how realistic or plausible their storyline is - or what version of a particular narrative it is drawn from.

2012: The CyArk Review

This concern with audience resonance (ticket sales) defines the final cut of the film 2012 itself - Chock-full of spectacular special effects and clocking in at two and a half hours, the film's editors seem to have cut a majority of the backstory that is heavily alluded-to on the film's promotional website. This website, which includes details on decades of preparation by the fictional IHC (Institute for Human Continuity) for the End Of The World, is far more influenced by millenarianist and New Age spiritualist ideas about 2012 than the archaeological narrative source material by Mayanist scholars. Regardless, very few of these details appear in the final film, which only refers a couple of times to the Maya calendars and their purported predictions of a "Galactic Alignment" (clearly modeled after John Major Jenkins' ideas in Maya Cosmosis 2012) that brings about the end of the world. Indeed, the main proponent of these ideas in the film is the character Charlie Frost, entertainingly portrayed as a burned-out hippie [millenarianist] by legendary loose-cannon actor Woody Harrelson; a character that reviewer Manohla Dargis, writing in the New York Times, humorously suggested might be modeled after New Age psychedelic journeyman Daniel Pinchbeck, author of 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl. Harrelson's fringe element turns out to be correct in the film, of course, but the intent seems at least as comedic as it is contemplative. In fact, the film's portrayal of The End of The World presents itself as almost an apocalyptic version of slapstick, in which seemingly-indestructible, wisecracking lead actor John Cusack speeds his family to safety in a series of high-speed vehicles as the earth's crust collapses in their wake.

|

In this promotional still frame from the Sony Pictures film 2012, family man Jackson Curtis (John Cusack) confronts millenarianist pirate radio broadcaster Charlie Frost as the Yellowstone supervolcano explodes right next to them. Charlie Frost's fictional radio show, This is the End, contains the film's only direct references to the Maya Calendar's supposed "end date" in 2012. |

2012 is relentlessly entertaining, a little exhausting at 2.5 hours in length, and utterly ridiculous. It plays shamelessly to our anxieties and intense curiosity about total apocalypse, a subject people have been fascinated by across countless cultures and vast spans of time. The film has practically nothing to do with the Maya calendar, which is relegated to a footnote in this piece of Hollywood showmanship. In this, the film 2012 is similar to and perhaps even more honest than other mass entertainment spectacles which involve stories and data adapted from archaeological narratives - it aims to be pure entertainment, and little more, feeding, exciting, and echoing our modern desires and fears while the year/date itself and its exotic origins serve as simple window dressing to a story about us - well, the Hollywood version of us, anyway.

Worries about The End

More worrisome than the film itself is public hysteria around the actual date of December 21 (or 23), 2012, which has generated a great deal of fear and, for some people who are a bit more emotionally fragile, threats of suicide (see this article from National Geographic for more examples and information). This hysteria has been fed by the makers of the film for the purpose of hyping it, and it is growing increasingly difficult (particularly on the internet) to find voices of reason in an often-sinister wilderness of open speculation on the subject.

Hopefully, this hysteria will subside as calmer heads prevail and make their voices heard. Though we have a more-than-excellent chance of waking up on December 22 (or 24), 2012, in the same shape as we were when we went to sleep, we might want to keep an eye on those of us who are a bit more impressionable than others. Take a moment to let these worriers know they should take all the scary things they are reading on the internet about 2012 with a grain of salt - or twenty. After all, the ancient Maya didn't seem concerned enough to really write much of anything about it. Should we?

References:

Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams

Lewin, Roger (2005). Human evolution: an illustrated introduction. Oxford:Wiley-Blackwell

In this promotional poster from <i>Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull</i> (2008), Harrison Ford's archaeologist Indiana Jones runs from a mob of scantily-clad Amazonian tribespeople while a giant crystal skull and a Maya-style step pyramid loom ominously in the background. The film is one of several in the first decade of the 21st century to incorporate aspects of ancient Maya culture to awe and entertain audiences; this has gone hand-in-hand with increasing public interest in the Maya generated by popular science books such as Jared Diamond's <i>Collapse: How Societies choose to Fail or Succeed</i> and <a href="http://archive.cyark.org/2012-end-of-the-world-perceptions-and-myths-blog">millenarianist</a>/<a href="http://archive.cyark.org/2012-new-age-predictions-blog">New age</a> phenomena such as the 2012 scare.

Promotional poster for the 1932 Boris Karloff film <i>The Mummy</i>. The film, widely-regarded as a classic, features a plot heavily-informed by Egyptian mythology, audience fascination with the concept of life after death, and what were perceived by the public to be cliff-hanging escapades by archaeologists in Egypt. The film was made a few years after archaeologist Howard Carter's discovery of the rich burial chamber of King Tut, an event chronicled for the New York World newspaper by journalist John L. Balderston - who wrote the script to <i>The Mummy</i> (<i>Vieira 55-58</i>).

In the 1986 film <i>Clan of the Cave Bear</i>, Darryl Hannah's Cro-Magnon character Ayla (shown in the movie poster here) is separated from her tribe and ends up living with Neandertals. The film attempted to tackle ambitious questions directly from paleoanthropology, including the question of whether Cro Magnon people (genetically the same as modern humans) and Neandertals (who were genetically distinct and went extinct around 22,000 years ago) could interbreed with each other.

- 104