Illuminating the Heritage of Old Paris

Early photographer's images provide rare views of the city before Haussmannization

March 12, 2014

Many are familiar with Les Miserables—Victor Hugo’s account of Paris’s poor struggling to survive—but few people know about photographer Charles Marville, who documented the Paris of Victor Hugo as it changed before everyone’s eyes. A native Parisian, born in 1813, Marville first worked as an illustrator before taking up photography, a new medium at the time. Hired as the official photographer for the city of Paris in 1862, Marville took on the monumental task of documenting the city as it underwent a massive transformation during the late 1800s.

Acting on orders from Emperor Napoleon III, Prefect of the Seine Georges-Eugène Haussmann destroyed and renovated an estimated 60% of the city of Paris. The aim of the program was to modernize the city; to make it healthier, and less congested. Haussmann’s plan included the installation of new sewers and the construction of bridges, public buildings, city infrastructure such as the famous ad kiosks, and a decadent opera house. In order to carry out his vision, Haussmann ordered the destruction of many historic neighborhoods and expanded the once narrow and winding city streets into wide boulevards. In a trend that continues to repeat itself today, the old was destroyed to make way for the new, but the city’s official photographer, Charles Marville, was able to document many of the places slated for destruction.

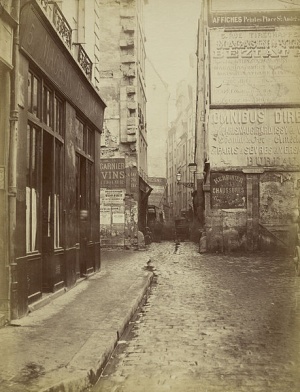

Thanks to Marville’s efforts, we can look at his photographs and trace Paris’s architectural history back to its medieval roots. We can see what life was like for the people who lived along the small, winding alleys, including the unpleasant reality of sewage running in the street. Marville’s photographs show the ways communities were uprooted during “Haussmannization”—large signs on shops thank their patrons and announce going out of business sales, or advertise moving crews. Several images depict the suburban wastelands where poor families, evicted from the slums of Paris to make room for new middle class apartments, hastily constructed haphazard shelters.

While Haussmann’s plan was ultimately perceived as a success, many Parisians at the time lamented the changes, believing people had become more detached from one another and had lost their connection to the city. Famous creative figures of the era, including Édouard Manet and Charles Baudelaire, expressed this feeling of loss in paintings and poems. Without Marville’s documentation, centuries of Paris’s architectural history would have been lost forever.

At CyArk, our work is driven by the conviction that heritage sites represent the collective memory of humanity. As Parisians in Haussmann’s day recognized, a community’s identity is tied to its heritage. When those ties are severed, who are we? While some perceive loss of heritage as inevitable, CyArk disagrees. Today we have the technology and tools to create a lasting record of heritage sites so that--in the worst-case scenario--even if they are lost, we will have a millimetrically accurate blueprint with which to rebuild them. And, in the best-case scenario, digitally preserving heritage sites furnishes site managers with powerful conservation and education tools to assist them in caring for a site more effectively and sharing its history and significance with a wider audience.

CyArk is proud to be picking up the torch of documentarians from generations past, like Marville, who saw the value of preserving heritage and whose foresight enriches our contemporary understanding of historic places and communities. Interested in learning more about Marville? New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently featuring an exhibit of his work, “Charles Marville: Photographer of Paris,” which will be on display through May 4.

Acting on orders from Emperor Napoleon III, Prefect of the Seine Georges-Eugène Haussmann destroyed and renovated an estimated 60% of the city of Paris. The aim of the program was to modernize the city; to make it healthier, and less congested. Haussmann’s plan included the installation of new sewers and the construction of bridges, public buildings, city infrastructure such as the famous ad kiosks, and a decadent opera house. In order to carry out his vision, Haussmann ordered the destruction of many historic neighborhoods and expanded the once narrow and winding city streets into wide boulevards. In a trend that continues to repeat itself today, the old was destroyed to make way for the new, but the city’s official photographer, Charles Marville, was able to document many of the places slated for destruction.

Thanks to Marville’s efforts, we can look at his photographs and trace Paris’s architectural history back to its medieval roots. We can see what life was like for the people who lived along the small, winding alleys, including the unpleasant reality of sewage running in the street. Marville’s photographs show the ways communities were uprooted during “Haussmannization”—large signs on shops thank their patrons and announce going out of business sales, or advertise moving crews. Several images depict the suburban wastelands where poor families, evicted from the slums of Paris to make room for new middle class apartments, hastily constructed haphazard shelters.

While Haussmann’s plan was ultimately perceived as a success, many Parisians at the time lamented the changes, believing people had become more detached from one another and had lost their connection to the city. Famous creative figures of the era, including Édouard Manet and Charles Baudelaire, expressed this feeling of loss in paintings and poems. Without Marville’s documentation, centuries of Paris’s architectural history would have been lost forever.

At CyArk, our work is driven by the conviction that heritage sites represent the collective memory of humanity. As Parisians in Haussmann’s day recognized, a community’s identity is tied to its heritage. When those ties are severed, who are we? While some perceive loss of heritage as inevitable, CyArk disagrees. Today we have the technology and tools to create a lasting record of heritage sites so that--in the worst-case scenario--even if they are lost, we will have a millimetrically accurate blueprint with which to rebuild them. And, in the best-case scenario, digitally preserving heritage sites furnishes site managers with powerful conservation and education tools to assist them in caring for a site more effectively and sharing its history and significance with a wider audience.

CyArk is proud to be picking up the torch of documentarians from generations past, like Marville, who saw the value of preserving heritage and whose foresight enriches our contemporary understanding of historic places and communities. Interested in learning more about Marville? New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently featuring an exhibit of his work, “Charles Marville: Photographer of Paris,” which will be on display through May 4.

"La Bièvre," photograph by Charles Marville, <br>circa 1865.

"Rue de Constantine, Paris," photograph by Charles Marville, circa 1865.

"Rue Tirechappe, View from the Rue Saint-Honoré," photograph by Charles Marville, 1860.