Tudor Place: Democracy Starts at Home

Peeling back the layers of a Neoclassical masterpiece and the architectural ideals that surround it

December 11, 2007

IMG1LAs a town so solidly rooted in 19th-century architecture, Washington, D.C., has no lack of Neoclassical flourishes—wide domes, stately columns, magnificent distances, and egalitarian symmetry. But almost as a rule, this isn’t seen in residences. The rapid pace of urban resettlement and renovation has taken its toll on the District of Columbia as it has in any city, leaving few residential relics of that era.

Tudor Place, Georgetown’s 200-year-old former home of the grandchildren of Martha Washington, is among the most significant early 19th-century residences in Washington and is receiving its first major renovation since 1914. The iconic home was designed by William Thornton, who created the first design for the U.S. Capitol and designed The Octagon House, now owned and operated as a museum by the American Architectural Foundation.

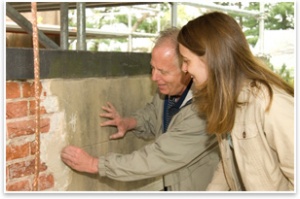

IMG2RLayer by layer

This restoration campaign is now in its second and most visible phase—removing and replacing its portland cement-based stucco. Built in 1816, its first application of stucco lasted until 1871, when owner Britannia Peter had it replaced. This application was undone by ivy that slowly inserted its way into cracks and pulled at the façade. In 1914, Britannia’s grandson, Armistead Peter Jr., completed a sweeping modernization of the house. He also replaced the lime-based stucco with portland cement supported by a metal lathe nailed into mortar boards. This unique reinforcement proved to be faulty and caused cracks in the cement. All this has put the underlying bricks and mortar in danger from exposure and extensive water damage.

The old stucco has been successfully removed, and the next step for Tudor Place is to have the muted gold sandstone stucco of 1914 replaced. Aiding this historic reconstruction are the extensive archival documents the museum houses. These include personal letters, financial documents, and original construction diagrams, many dating back to the Washingtons themselves. All of these have helped the museum staff peel away the layers of history and accurately interpret the history of Tudor Place—a history that has had to rely on anecdotal evidence for too long. “The more you know about the materials you’re dealing with, the better you’re able to estimate costs of the project and the possible surprises that might come up,” says Jana Shafagoj, the site’s architectural historian.

Shafagoj will also be aided by 3D-photogrammetry technology, provided by Cyark, a digital documentation company. This uses a laser to scan the exterior and interior of the building to produce a microscopically accurate 3D model of everything, including the exposed brick faces, visible for the first time since construction. “Instead of looking only at one elevation of the building, this creates the whole house so you can really turn it and examine how different portions of interrelate with each other,” Shafagoj says.

IMG3LExpression of democratic ideals

This example of Federalist architecture finds its most obvious expression in the south temple portico, which looks down at (and possibly on) what was the Port of Georgetown. Though designed as an example of a young, egalitarian democracy, the south face features masonry flourishes (Flemish brick bonds, delicately shaped three-point mortar joints) meant to flaunt the resident’s wealth and not seen anywhere else on the house.

Thornton’s design for Tudor Place was a Palladian five-block symmetrical plan, with a two-story central block, one-story “hyphen,” and one-and-a-half story wings on each side. Like his U.S. Capitol design, Tudor Place is a paragon of Neoclassical, or distinctly American “Jeffersonian,” architecture, embodiments of when talented statesmen and amateur architects built Greek and Roman-styled temples to democracy inspired by the ancient Republics and the self-determination for which they stood. They (like Tudor Place) were to be purely American spaces, equal and balanced to demonstrate the transparent openness of American government. Thornton, although a physician by profession, was no amateur “gentleman architect,” but a serious practitioner from an era when architecture was becoming increasingly professionalized. Though he possessed an exceptional visual memory, he was no mere “copyist” of Classical forms, and instead took broad inspiration from European Neoclassicalists like Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Robert Adams, according to Thornton editor and historian C.M. Harris.

Charles Atherton, the late chief administrative officer of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, recognized Thornton’s and Jefferson’s contributions as singularly vital links to history. “What other architects of other great homes have such a singular connection with the beginning of this country?” he asked. “One and only one comes to mind: Jefferson and his Monticello.”

A broad conservation period

The interior is just as self-conscious about its philosophical concerns as the exterior. Faux-Greek artifacts abound, like the gold and maroon urns flanking the rear entrance to the temple portico that featuring graceful figures in robes carrying harps. Several such artifacts were made in the 1810s and can be considered just as legitimately “Neoclassical” as the dome of the portico outside.

Though surrounded by such priceless artifacts, Shafagoj’s conservation mission isn’t stuck in any particular era. The historical period of conservation for the Tudor Place is from 1816 to 1983—the entire period when generations of the Peter family lived there. This means preserving the stucco on the walls as well as the bidet in the bathroom. “Something that was installed here in 1816 is just as important as something installed in 1982,” says Shafagoj.

Tudor Place, Georgetown’s 200-year-old former home of the grandchildren of Martha Washington, is among the most significant early 19th-century residences in Washington and is receiving its first major renovation since 1914. The iconic home was designed by William Thornton, who created the first design for the U.S. Capitol and designed The Octagon House, now owned and operated as a museum by the American Architectural Foundation.

IMG2RLayer by layer

This restoration campaign is now in its second and most visible phase—removing and replacing its portland cement-based stucco. Built in 1816, its first application of stucco lasted until 1871, when owner Britannia Peter had it replaced. This application was undone by ivy that slowly inserted its way into cracks and pulled at the façade. In 1914, Britannia’s grandson, Armistead Peter Jr., completed a sweeping modernization of the house. He also replaced the lime-based stucco with portland cement supported by a metal lathe nailed into mortar boards. This unique reinforcement proved to be faulty and caused cracks in the cement. All this has put the underlying bricks and mortar in danger from exposure and extensive water damage.

The old stucco has been successfully removed, and the next step for Tudor Place is to have the muted gold sandstone stucco of 1914 replaced. Aiding this historic reconstruction are the extensive archival documents the museum houses. These include personal letters, financial documents, and original construction diagrams, many dating back to the Washingtons themselves. All of these have helped the museum staff peel away the layers of history and accurately interpret the history of Tudor Place—a history that has had to rely on anecdotal evidence for too long. “The more you know about the materials you’re dealing with, the better you’re able to estimate costs of the project and the possible surprises that might come up,” says Jana Shafagoj, the site’s architectural historian.

Shafagoj will also be aided by 3D-photogrammetry technology, provided by Cyark, a digital documentation company. This uses a laser to scan the exterior and interior of the building to produce a microscopically accurate 3D model of everything, including the exposed brick faces, visible for the first time since construction. “Instead of looking only at one elevation of the building, this creates the whole house so you can really turn it and examine how different portions of interrelate with each other,” Shafagoj says.

IMG3LExpression of democratic ideals

This example of Federalist architecture finds its most obvious expression in the south temple portico, which looks down at (and possibly on) what was the Port of Georgetown. Though designed as an example of a young, egalitarian democracy, the south face features masonry flourishes (Flemish brick bonds, delicately shaped three-point mortar joints) meant to flaunt the resident’s wealth and not seen anywhere else on the house.

Thornton’s design for Tudor Place was a Palladian five-block symmetrical plan, with a two-story central block, one-story “hyphen,” and one-and-a-half story wings on each side. Like his U.S. Capitol design, Tudor Place is a paragon of Neoclassical, or distinctly American “Jeffersonian,” architecture, embodiments of when talented statesmen and amateur architects built Greek and Roman-styled temples to democracy inspired by the ancient Republics and the self-determination for which they stood. They (like Tudor Place) were to be purely American spaces, equal and balanced to demonstrate the transparent openness of American government. Thornton, although a physician by profession, was no amateur “gentleman architect,” but a serious practitioner from an era when architecture was becoming increasingly professionalized. Though he possessed an exceptional visual memory, he was no mere “copyist” of Classical forms, and instead took broad inspiration from European Neoclassicalists like Claude Nicolas Ledoux and Robert Adams, according to Thornton editor and historian C.M. Harris.

Charles Atherton, the late chief administrative officer of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, recognized Thornton’s and Jefferson’s contributions as singularly vital links to history. “What other architects of other great homes have such a singular connection with the beginning of this country?” he asked. “One and only one comes to mind: Jefferson and his Monticello.”

A broad conservation period

The interior is just as self-conscious about its philosophical concerns as the exterior. Faux-Greek artifacts abound, like the gold and maroon urns flanking the rear entrance to the temple portico that featuring graceful figures in robes carrying harps. Several such artifacts were made in the 1810s and can be considered just as legitimately “Neoclassical” as the dome of the portico outside.

Though surrounded by such priceless artifacts, Shafagoj’s conservation mission isn’t stuck in any particular era. The historical period of conservation for the Tudor Place is from 1816 to 1983—the entire period when generations of the Peter family lived there. This means preserving the stucco on the walls as well as the bidet in the bathroom. “Something that was installed here in 1816 is just as important as something installed in 1982,” says Shafagoj.