The Al Nuri Legacy and Project Anqa

Last week the team was filled with sadness to learn of the destruction of the al-Nuri Mosque in Mosul, in addition to the devastating loss of life and humanitarian crisis faced by those living in Mosul. The Mosque along with its iconic leaning minaret, called Al Hadba or the hunchback, had long been a symbol of the city of Mosul. Named after its builder, Nur al-Din al-Zengi a prince of the Seljuk Empire, the Al-Nuri Mosque joins a long list of heritage sites damaged and destroyed in the last two years in the Middle East.

In the wake of this destruction, it can be difficult to put into perspective the objective that our Project Anqa team has been working so hard to achieve. Project Anqa is a collaboration between CyArk, ICOMOS and Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH) to use 3D digital technologies to proactively record at-risk cultural heritage sites throughout the Middle East and North Africa. With support from the Arcadia Foundation, we have begun the work to document sites in Syria with the collaboration of the UNESCO Beirut field office and the Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums in Syria. The work in Damascus was envisioned to act as a “Noah’s Ark” of sorts to survey and document the diversity of monuments within ancient Damascus.

With so many sites under threat in the region, it seems we have only just scratched the surface of the work needed in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and several other countries in the region. But rather than despair, this week I became increasingly hopeful after I received a message from Samir Abdulac, ICOMOS Secretery General of France and member of the Project Anqa team. Samir reminded many of us working on the project that we were already working to care for the Nur al Din legacy through the work we are doing in Damascus, where several of the buildings in the old city also bear his name.

Samir shared that “Once upon a time, Nur al Din al-Zengi, a wise prince gathered under his rule Mosul, Aleppo, Damascus and even namely Cairo. History books don’t always mention his construction activity. One has to to look into local guidebooks and manuals to find them mentioned. What has struck me was “ al Nuri,” such a familiar name, [is] also attached to some of renowned monuments of Damascus . I should have guessed so before but it is like recognizing a cousin only on his deathbed.”

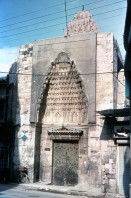

The loss of al-Nuri Mosque is profound. Monuments provide a tangible connection with the past and the people that came before us, but the legacy of a monument is not lost with its destruction. It’s value to the people of Iraq can not be so easily erased and its architectural and stylistic importance are mirrored throughout the region in other Seljuk buildings built under Nur al-Din including those in Damascus. Two such buildings, the Bimaristan al Nuri and the Hammam al Nuri in the old city of Damascus, are actively being documented by our colleagues at the DGAM.