2012: Maya Perspectives and Cultural Remains

Part Four (Section A) of Five - The Maya

November 5, 2009

We have discussed some aspects of the public fascination, hype and hysteria surrounding the upcoming date of December 21 (or 23!), 2012 over the previous posts in this series: Introduction, Millenarianism, and Pan-Shamanism. This date was translated from an ancient Maya calendar, and is believed by many to be a harbinger of great change, potentially destructive and transformative in nature. New Age and Millenarianist-style media have provided much of the fuel for a growing fire of curiosity and concern about 2012, a fire which is now being fed by the entertainment industry for the purpose of selling a sensational product to a willing public. After all, as we've said before, who doesn't like a good end-of-the-world movie based on a fantastic supernatural myth?

The fears and concepts of modern, western culture have been grafted onto a far earlier and vastly different culture's belief system. In doing so, we have unfortunately ended up with invented myths that look an awful lot like other western myths - but not like those of the ancient Maya. A brief look at what we know of this fascinating culture can easily prove as compelling as any Hollywood blockbuster. As we are discussing a complex subject, this post is lengthier than the others and thus split into two sections (A and B). Hopefully it will provide the reader with a greater insight into the world of the Maya people. For a quick overview, read the bolded passages.

A side note on terms: The word "Maya" is used when referring to the people, while "Mayan" is used when referring to their language(s) - either written or spoken.

An increasing number of parallels have been drawn by modern theorists between current western society and that of the ancient Maya of the Late Preclassic and Classic periods. This legendary civilization achieved its greatest lasting world prominence by erecting enormous independent city-states in the lowland Petén region of present-day Guatemala and Belize. This grand civilization lasted from a few hundred years BCE until around 900 CE. This time period is called Terminal Classic, and is more popularly known as the "Maya Collapse" (Henderson 114, 139, 199). Starting around 800 CE and continuing over the next century, the region's cities were abandoned by most of their inhabitants following three severe droughts, overpopulation, over-extension of natural resources, increasing demands from a threatened elite for public construction, and intensified warfare (Sharer 355-357, Henderson 236-239) (also see Ashley Richter's post for some of the latest research on ancient deforestation around the metropolis of Tikal). The great scale and relative rapidity of these abandonments has given us interesting grist for thought pertaining to questions of modern civilization's long-term sustainability, particularly with regard to unsustainable use of natural resources. The most popular credible work of scholarship to explore this subject is Jared Diamond's book Collapse - How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed.

Though their society experienced substantial hardship during the end of the first millennium CE, the Maya did not simply "disappear". Rather, they migrated in great numbers, creating a diaspora that established new cities and increased the populations of older ones in areas peripheral to the Petén Region. Popular areas of settlement included the Yucatan, the coast of modern-day Belize, and Highland Guatemala (which had been considered a Maya heartland since several hundred years before the rise of cities in the lowland Petén)(Sharer 357-358, 368; Henderson ibid.). While transformative social upheavals seem to have occurred frequently thoughout the first millennium and early in the second millennium CE, it was the period of European conquest, which began in this area in 1519, that unquestionably resulted in the greatest concentrated loss of traditional knowledge since the Maya culture's earliest known inception. This is in many ways the story of most of the indigenous cultures of the Americas (Henderson 259; Coe 202-205). With the Spanish conquistadors came forced Christianization, land seizures, forced relocations, enslavement under the encomienda system, the burning of nearly all of the Maya sacred codexes (bark-paper books), destruction of monuments, language suppression, and more. This all added up to an incalculable loss of heritage for the Maya (deLanda 157-160).

This cultural suppression has continued into modern times under various guises (Coe 208-212; Womack 87-104, 340-354). However, nearly five centuries of repression have not succeeded in eliminating this proud people: Six million speakers of over 22 Mayan languages live in the region today, a number that is thought to be far greater than their numbers at the time of the Spanish Conquest (Van Stone I-13).

While the Maya cultures and belief systems of 21st-century Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico's Yucatan and Chiapas share numerous commonalities with their distant ancestors, all cultures change over time. The Maya's turbulent history since the Spanish Conquest has created great rifts in modern knowledge of many of their older belief systems (Warren 148-162, 189-191). Fortunately for both global scholarship and the modern Maya people, the ancient Maya developed a complex writing system that has endured to the present-day. This writing system was carved into stone monuments and small objects, painted on cave walls and pottery, and inscribed in the four known Maya codexes that survived the great book-burning of the 16th century. Despite their fragmentary and incomplete nature, these resources have provided a great deal of information about the histories of ruling lineages of different Maya kingdoms. They have also provided valuable insight into the supernatural forces and different realms that existed in Maya cosmology and prophesies. (Henderson 21-23).

The complex glyphic writing system of the ancient Maya is considered to be logographic, which means it uses both syllables from ancient Mayan dialects (particularly Yukatekan and Ch'olan) and symbols that represent whole words or concepts (Montgomery 2002:5-6; Henderson 19-21). Many of the Maya calendar and numerical glyphs have only been partially understood since the time of the Spanish Conquest, and it wasn't until the breakthroughs of scholars Yuri Knorosov and Tatiana Proskouriakoff in the 1950s and 1960 that we began to really understand the Mayan syllabic and word glyphs. This understanding enabled scholars to accurately decipher Maya calendar and numerical glyphs. Unfortunately, much of the confusion over these dates persists from inaccurate translations that occurred before the 1950s (Henderson 18-20, Coe 194-195).

The bulk of Mayan inscriptions and calendar dates that we have access to today are from stone carvings in the great ruined cities of the Maya Classic Period, located in the vast lowland jungles of Petén and its peripheral areas - Palenque, Yaxchilan, Tikal, Caracol, Copan, Calakmul (ibid. 111, 139-140). It is from a combination of information from their Long Count calendar dates (used almost exclusively during the Late Preclassic and Classic periods), and the more-recently deciphered vocabulary, that we have derived a great deal of our information about the history and society of the ancient Maya. This includes dates and numbers of significance (Rice 40-45). Does that include December 21 (or 23), 2012? We take a look at that in the next blog...

Next up...Part IV, section B : The Maya Calendars

References:

Henderson, John (1997). The World of the Ancient Maya: Second Edition. Ithaca:Cornell University Press

Sharer, Robert J. (1994). The Ancient Maya: Fifth Edition. Stanford:Stanford University Press

Coe, Michael D. (1993). The Maya: Fifth Edition. New York:Thames and Hudson

deLanda, Friar Diego (1978 org. 1566). Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Mineola (New York):Dover Publications

Womack, John (1999). Rebellion in Chiapas: an Historical Reader. New York:The New Press

Van Stone, Mark (2008). It's Not the End of the World: What the Ancient Maya Tell Us About 2012. Located online at the Foundation For The Advancement Of Mesoamerican Studies website.

Warren, Kay B. (1998). Indigenous Movements and Their Critics: Pan-Maya Activism in Guatemala. Princeton:Princeton University Press.

Montgomery, John (2002). Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York:Hippocrene Books

Rice, Prudence M. (2007). Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin:University of Texas Press

Carrasco, Michael (2004). Unaahil B'aak: The Temples of Palenque. Located online at the Wesleyan University Website

The fears and concepts of modern, western culture have been grafted onto a far earlier and vastly different culture's belief system. In doing so, we have unfortunately ended up with invented myths that look an awful lot like other western myths - but not like those of the ancient Maya. A brief look at what we know of this fascinating culture can easily prove as compelling as any Hollywood blockbuster. As we are discussing a complex subject, this post is lengthier than the others and thus split into two sections (A and B). Hopefully it will provide the reader with a greater insight into the world of the Maya people. For a quick overview, read the bolded passages.

A side note on terms: The word "Maya" is used when referring to the people, while "Mayan" is used when referring to their language(s) - either written or spoken.

What happened to the Maya?

An increasing number of parallels have been drawn by modern theorists between current western society and that of the ancient Maya of the Late Preclassic and Classic periods. This legendary civilization achieved its greatest lasting world prominence by erecting enormous independent city-states in the lowland Petén region of present-day Guatemala and Belize. This grand civilization lasted from a few hundred years BCE until around 900 CE. This time period is called Terminal Classic, and is more popularly known as the "Maya Collapse" (Henderson 114, 139, 199). Starting around 800 CE and continuing over the next century, the region's cities were abandoned by most of their inhabitants following three severe droughts, overpopulation, over-extension of natural resources, increasing demands from a threatened elite for public construction, and intensified warfare (Sharer 355-357, Henderson 236-239) (also see Ashley Richter's post for some of the latest research on ancient deforestation around the metropolis of Tikal). The great scale and relative rapidity of these abandonments has given us interesting grist for thought pertaining to questions of modern civilization's long-term sustainability, particularly with regard to unsustainable use of natural resources. The most popular credible work of scholarship to explore this subject is Jared Diamond's book Collapse - How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed.

Though their society experienced substantial hardship during the end of the first millennium CE, the Maya did not simply "disappear". Rather, they migrated in great numbers, creating a diaspora that established new cities and increased the populations of older ones in areas peripheral to the Petén Region. Popular areas of settlement included the Yucatan, the coast of modern-day Belize, and Highland Guatemala (which had been considered a Maya heartland since several hundred years before the rise of cities in the lowland Petén)(Sharer 357-358, 368; Henderson ibid.). While transformative social upheavals seem to have occurred frequently thoughout the first millennium and early in the second millennium CE, it was the period of European conquest, which began in this area in 1519, that unquestionably resulted in the greatest concentrated loss of traditional knowledge since the Maya culture's earliest known inception. This is in many ways the story of most of the indigenous cultures of the Americas (Henderson 259; Coe 202-205). With the Spanish conquistadors came forced Christianization, land seizures, forced relocations, enslavement under the encomienda system, the burning of nearly all of the Maya sacred codexes (bark-paper books), destruction of monuments, language suppression, and more. This all added up to an incalculable loss of heritage for the Maya (deLanda 157-160).

This cultural suppression has continued into modern times under various guises (Coe 208-212; Womack 87-104, 340-354). However, nearly five centuries of repression have not succeeded in eliminating this proud people: Six million speakers of over 22 Mayan languages live in the region today, a number that is thought to be far greater than their numbers at the time of the Spanish Conquest (Van Stone I-13).

Remains of the Maya Written Language

While the Maya cultures and belief systems of 21st-century Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico's Yucatan and Chiapas share numerous commonalities with their distant ancestors, all cultures change over time. The Maya's turbulent history since the Spanish Conquest has created great rifts in modern knowledge of many of their older belief systems (Warren 148-162, 189-191). Fortunately for both global scholarship and the modern Maya people, the ancient Maya developed a complex writing system that has endured to the present-day. This writing system was carved into stone monuments and small objects, painted on cave walls and pottery, and inscribed in the four known Maya codexes that survived the great book-burning of the 16th century. Despite their fragmentary and incomplete nature, these resources have provided a great deal of information about the histories of ruling lineages of different Maya kingdoms. They have also provided valuable insight into the supernatural forces and different realms that existed in Maya cosmology and prophesies. (Henderson 21-23).

The complex glyphic writing system of the ancient Maya is considered to be logographic, which means it uses both syllables from ancient Mayan dialects (particularly Yukatekan and Ch'olan) and symbols that represent whole words or concepts (Montgomery 2002:5-6; Henderson 19-21). Many of the Maya calendar and numerical glyphs have only been partially understood since the time of the Spanish Conquest, and it wasn't until the breakthroughs of scholars Yuri Knorosov and Tatiana Proskouriakoff in the 1950s and 1960 that we began to really understand the Mayan syllabic and word glyphs. This understanding enabled scholars to accurately decipher Maya calendar and numerical glyphs. Unfortunately, much of the confusion over these dates persists from inaccurate translations that occurred before the 1950s (Henderson 18-20, Coe 194-195).

The bulk of Mayan inscriptions and calendar dates that we have access to today are from stone carvings in the great ruined cities of the Maya Classic Period, located in the vast lowland jungles of Petén and its peripheral areas - Palenque, Yaxchilan, Tikal, Caracol, Copan, Calakmul (ibid. 111, 139-140). It is from a combination of information from their Long Count calendar dates (used almost exclusively during the Late Preclassic and Classic periods), and the more-recently deciphered vocabulary, that we have derived a great deal of our information about the history and society of the ancient Maya. This includes dates and numbers of significance (Rice 40-45). Does that include December 21 (or 23), 2012? We take a look at that in the next blog...

Next up...Part IV, section B : The Maya Calendars

References:

Henderson, John (1997). The World of the Ancient Maya: Second Edition. Ithaca:Cornell University Press

Sharer, Robert J. (1994). The Ancient Maya: Fifth Edition. Stanford:Stanford University Press

Coe, Michael D. (1993). The Maya: Fifth Edition. New York:Thames and Hudson

deLanda, Friar Diego (1978 org. 1566). Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. Mineola (New York):Dover Publications

Womack, John (1999). Rebellion in Chiapas: an Historical Reader. New York:The New Press

Van Stone, Mark (2008). It's Not the End of the World: What the Ancient Maya Tell Us About 2012. Located online at the Foundation For The Advancement Of Mesoamerican Studies website.

Warren, Kay B. (1998). Indigenous Movements and Their Critics: Pan-Maya Activism in Guatemala. Princeton:Princeton University Press.

Montgomery, John (2002). Dictionary of Maya Hieroglyphs. New York:Hippocrene Books

Rice, Prudence M. (2007). Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin:University of Texas Press

Carrasco, Michael (2004). Unaahil B'aak: The Temples of Palenque. Located online at the Wesleyan University Website

Donate $5 to CyArk

Help CyArk preserve more sites by making a small donation.

Pages 69 and 61 from the 11th-century CE <i>Dresden Codex</i>, one of the few Mayan-language bark-paper Codexes to survive the mass book-burning ordered by then-Bishop Diego deLanda. These parallel texts form "Serpent Number Tables", with the deity Chaak and a rabbit scribe deity sitting atop six-digit "Distance Numbers" counting forward from a date almost 40,000 years in the past, well before the current creation date of 3114 BCE (<i>Van Stone II-105</i>).

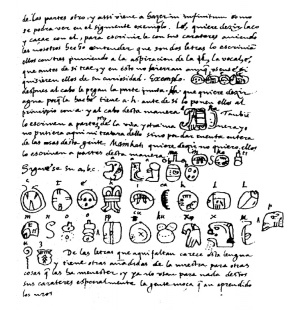

The famous "Landa Alphabet", written down by Spanish Friar Diego deLanda in his 16th-century manuscript <i>Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán</i> - a vital early piece of European scholarship concerning the Maya. DeLanda attempted to have a Mayan-speaking informant write a glyphic alphabet that directly corresponded to our own Greco-Roman one. What he ended up with, however, was much closer to a syllabary; something that scholars did not figure out until the mid-20th century. Amusingly, deLanda demanded that the informant/scribe, Gaspar Antonio Chi, also write a complete sentence in Mayan for him after the alphabet, a sentence deLanda did not realize stated "I don't want to write anything" (<i>Carrasco Intro.</i>)

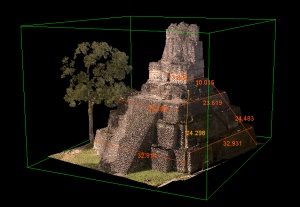

Photo-textured 3D laser scan elevation of Temple II at the great Maya city of <a href="http://archive.cyark.org/tikal-intro">Tikal</a>, showing measurements and dimensions for this Step pyramid. From inscriptions related to this monument, we now know that the eighth-century Tikal king Jasaw Chan K'awiil I commissioned Temples I and II during his reign. Temple II is dedicated to his wife, Lady Twelve Macaw (died 704 CE), and she is interred within it. Image from Cyark.