2012: Understanding The Maya Calendars

Section B of Part 4 (of Five) - The Long Count

November 11, 2009

This is Section B of the three-section Part IV of the 2012 Blog Series from CyArk (click here for Section A)...Yes, that is a bit confusing, but so is the Maya calendar - at least to our eyes. Be aware that these next two entries are going to be a bit challenging. Stick to the Bold Text if you want a quick overview, but if you make it through the whole thing you'll be an expert.

Scholars were able to read the Maya calender inscriptions before the rest of the ancient Maya glyphs because two of their calendars, the Tzolk'in and Haab', are still in use by traditional timekeepers in Mesoamerica, particularly in the Maya region (Rice 49). Also, the Tzolk'in and the Haab' calendars match the Aztecs' 260-day Tonalpohualli and 365-day Xiuhpohualli calendars in many ways. As the Aztecs are a particularly well-documented pre-Colombian culture, knowledge of their calendars helped early scholars make sense of the Maya ones (Rice 30-33).

The 260-day Tzolk'in is the older calendar of the two and is thought to have existed from at least as early as 1600 BCE (Rice 33). It begins with a number from 1 to 13 attached to one of 20 named days in succession, each with its own glyph. The Tzolk'in's numerals and days can be combined to create 260 different variations before the same day and number combination are repeated in the cycle (Van Stone IV-6; Rice 31). Scholars are not precisely sure what the 260-day period correlates to, but theories include agricultural cycles, the gestation period of human pregnancy, and the movements of celestial bodies (particularly Venus). The mythically-charged Tzolk'in is generally referenced by its supporters for divinations of the supernatural (Rice 33-34; Van Stone IV-22).

The Haab' calendar is roughly equivalent to our own 365-day solar year. It operates similarly to the Tzolk'in, but instead of a 13 by 20 combination system (to make 260 days), it uses 18 by 20 to arrive at 360 days. Five extra days called wayeb' are tacked on at the end for a full 365 days. Something like months, the 18 periods of the Haab' are called winals, and each winal has 20 days (called k'in), which make a 360-day tun. The wayeb at the end of the year translate loosely as "dark" or "dangerous" (Van Stone IV-18). The earliest written evidence of the Haab' dates to the 6th century BCE in Oaxaca but it was likely in use long before that (Rice 45-46; Montgomery 2003:19). The Haab' correlates very closely to the approximately 365-day solar year but does not factor in an extra day every four years, a "leap year", as our Gregorian calendar does (ibid. 42). Most Maya dates are expressed as a combination of Tzolk'in and Haab'; the Aztec, in contrast, mainly used the Tzolk'in, and the Haab' appeared only rarely (Van Stone IV-20, 41).

The Tzolk'in and Haab' calendars interlock with each other like gears in a clock, in the interval known by Mayanists as the Calendar Round. During this round it takes a total of 37,960 days (52 years) before the same day names and numbers coincide in both calendars again (Rice 31). For the measurement of greater periods of time, however, there was a third Maya calendar. This calendar has no specific name that we are yet aware of, so Mayanist scholars have termed it the Long Count Calendar. Unlike the Calendar Round, which is still in use in some Maya communities, the Long Count Calendar fell out of use over 1000 years ago following the end of the Classic Period, and for the most part has only been readable by modern people for the past 80 years. This is thanks to the preeminent Mayanist Sir Eric Thompson, who cracked important parts of its glyphic code (Henderson 283, Van Stone IV-39).

The Long Count, like the 52-year Calendar Round, involves the interlocking cycles of the ever-repeating Tzolk'in and Haab', but it fixes them within a far longer range of time. This range is based upon an actual year with a set origin date - much like our Common Era (AD or CE) system currently tells us it has been 2009 years since the birth of Jesus Christ (Montgomery 2003:5). Long Count inscriptions start with what Mayanist scholars term the Initial Series Introducing Glyph (ISIG), a distinct, large glyph that tells us a date is about to be recorded (Montgomery 2003:5-6; Rice 172). This glyph is followed by other glyphs, each with a corresponding number to indicate the specific number of time units elapsed in each discrete category. These start at the top with the largest time units and go all the way down to the individual Calendar Round (Tzolk'in and Haab') dates, creating a system that measures over thousands of years right down to the specific day being recorded (Montgomery 2003:5).

Understanding the Long Count system is not easy, but there are some parallels that can be drawn to the Gregorian Calendar which can help. In our current system, the most common numeric expression of a date uses three units: day, month, year. Dates in our Gregorian Calendar format can be written in a number of ways, but for our purposes, we'll express November 12th, 2009 as 12.11.2009. The Maya had more than three units, and if one were so inclined, so too could we. If you wanted to add more time units to our system, the easiest thing to do is break the year 2009 into centuries and single years. This creates a date that looks like this: 12.11.09.20. Now, if we wanted to make something more similar to the Long Count, we would do it a little differently - we would reverse the order of the numbers, add a millennia unit and break apart the centuries and decades, then place the specific day and month at the end as they are the units that repeat periodically. So what we have looks like this: 2.0.0.9 November the 12th - Thursday. Functionally, this is much the same as the Long Count date 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 3 K'ank'in, which equals the date December 21 (or 23), 2012 - but with some key differences.

The Maya Long Count has 5 units of time, each going up to 20 before adding a number to the bigger unit and flipping over to zero - this is in contrast to our system, in which numbers switch over after they hit 10 (i.e., 2.0.0.9 becomes 2.0.1.0). The five Maya Long Count units are named and organized as follows, starting from the right and going to the left: The k'in is a single day, which makes up the last digit in the series and goes up to 20. Positioned before the k'in is the winal count, each number of which equals 20 kins (a bit like short months). The winal is the only unit position that flips back to zero before it reaches 20, and in keeping with the divisible-by-20 format, the tun is made up of 18 winals or 360 k'in for a rough approximation of the solar year; this does not factor in the 5 "dark days" (wayeb') at the end of the year. Positioned before the tun is the k'atun, made up of 20 tuns, and positioned at the beginning of the series right after the ISIG is the b'aktun of 20 k'atuns - just short of 400 years (Montgomery 2003:40-43).

Written in our numerical system, a date from the Long Count would look something like this: 9.12.17.0.6, which would mean 9 b'aktuns, 12 k'atuns, 17 tuns, zero winals, and 6 k'ins, signifying the total amount of time that had passed since the fixed beginning date of the Long Count (ibid. 42). The earliest recorded complete Initial Series date yet found comes from the Gulf Coast Olmec culture site of Tres Zapotes, where a monument known as Stela C records an Initial Series date of 7.16.6.16.18 6 Etz'nab', which is equivalent to September 3rd (or 5th), 32 BCE (Rice 103). The earliest Long Count date from the central Maya lowlands (Peten region) is the date 8.12.14.8.15, found on Stela 29 at the city of Tikal and correlating to 292 CE (Henderson 116).

The current fixed point in time from which the Long Count Initial Series measures is a 4 Ajaw 8 Kumk'u day (Tzolk'in and Haab' dates, respectively) almost 13 b'aktuns ago, with the Long Count date being recorded as 13.0.0.0.0 - NOT 0.0.0.0.0 as would be expected; for whatever reason, the ancient Maya believed that the Long Count calendar reset itself at the end of a previous 13 b'aktun, 5125-year cycle rather than a 20 b'aktun 7885-year cycle (Rice 147; Van Stone FAQs). In our Gregorian calendar, this date corresponds to August 11th, 3114 BCE, though Mayanist scholars are split on whether to use a more recently-developed calendar correlation that sets the date two days later on August 13th (Rice 172; Van Stone IV-39; Montgomery 2003:43-44).

Either way, this date is well before the development of Maya civilization or its antecedents such as the Olmec, and is mythic in origin, probably based at least partially around numerology pertaining to the number 13 and perhaps agricultural associations with maize (corn) harvesting in August (Rice 176). Though the religious elites of different Classic Period Maya cities interpreted the calendars in different ways with widely-varying conclusions, this particular date held widespread significance as the creation point of the current world, while other dates referenced before this event stretch deeply back into time and earlier creations. In the case of Stela 1 in the city of Macanxoc, an event is recorded with a date stretching 13 periods earlier than 13.0.0.0.0, back to 13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.0.0.0.0 - a period of 41,943,040,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years (Montgomery 2003:80-84). In the ancient Maya worldview, there were many creations before our current world came into existence, but clearly they believed something significant was there in the distant past before the current agreed-upon origin point in 3114 BCE.

The Long Count date 13.0.0.0.0, falling on a 4 Ahau 3 K'ank'in Calendar Round date, will be replicated on December 21st (or 23rd), 2012. Maya epigraphers (experts on the glyphic inscriptions) have been aware of this upcoming date for decades. The limited records we have of ancient Maya k'atun endings (approximately 20 years) indicate that they would have celebrated this date with the construction of new monuments, a layer of fresh stucco and paint on existing buildings, veneration of ancestors, and public festivities and rituals (Rice 177-178, Sharer 546-547). Many people, particularly millenarianists and New Age spiritualists, believe that since the previous creation ended after 13 b'aktuns, the current creation will end at that point as well. The current glyphic evidence, however, provides little or no indication that the Maya believed anything will happen at the end of this particular 5125-year period (Van Stone III; Montgomery 2003:86; Houston 2008). Many experts in Maya studies believe, from written evidence at different sites, that the ancient Maya believed their Long Count calendar's b'aktun unit would simply reset (like a clock striking midnight), add a new upper-level time unit (a piktun of 13 b'akuns) and a new period of time will start, with life continuing on much as before following recognition of the period ending - but will the calendar actually reset after 13 b'aktuns this time?

There is substantial written evidence, from the ruins of major ceremonial centers, to indicate that the current b'aktun unit will not reset after it hits 13. Numerous dates in the future well after 2012 are frequently referenced in Classic Period Maya inscriptions, which almost always place emphasis on “impersonal temporal events that are safely predictable”; less action-oriented than purely calendrical (Houston and Stuart 1996:301). For example, 7th-century glyphs in the great Maya city of Palenque's Temple of the Inscriptions predict celebrations on the date 1.0.0.0.0.8 (over 4000 years into the future) surrounding the 80th Calendar Round anniversary of the coronation of Palenque's king Pakal Shield who is buried beneath the Temple. In this case, the Temple's carvers worked under the assumption that the b'aktuns would continue up past 13 to 20 (as 80 Calendar Rounds would have equalled up to an additional 6 b'aktuns), at which point it would flip to zero and a higher-order unit (a piktun) of 1 would be added to make for a total of 6 digits in the date (1.0.0.0.0.0) rather than our current 5 (which is 12.19.16.15.1 for the year 2009)(Van Stone II-85, Carrasco 2004). Thus, the carvers at Palenque believed the momentous period-ending was not set for the year 2012 but the year 4772; and the fact that they believed people after that point would be celebrating Pakal's reign indicates they had no reason to think there would any drastic break with the traditions of the past. Meanwhile, over at the Mesoamerican metropolis of Tikal, there is a monument bearing a date with the b'aktun position set to 19, 6 positions in the future beyond the upcoming 13.0.0.0.0 date and, again, indicating the calendar will not flip in 2012 as commonly believed (Van Stone II-97).

So...What DO the ancient Maya have to say about 2012 in their texts? Read on...

References:

Rice, Prudence M. (2007). Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin:University of Texas Press

Montgomery, John (2003). Cycles In Time: The Maya Calendar. Antigua (Guatemala):Editorial Laura Lee

Van Stone, Mark (2008). It's Not the End of the World: What the Ancient Maya Tell Us About 2012. Located online at the Foundation For The Advancement Of Mesoamerican Studies website.

Henderson, John (1997). The World of the Ancient Maya: Second Edition. Ithaca:Cornell University Press

Houston, Stephen (2008). What Will Not Happen In 2012. Online at Maya Decipherment epigraphy weblog.

Houston, Stephen and Stuart, David (1996). Of Gods, Glyphs, and Kings: Divinity and Rulership among the Classic Maya. Antiquity Magazine #70:289-312

Carrasco, Michael (2004). Unaahil B'aak: The Temples of Palenque (Temple of Inscriptions). Located online at the Wesleyan University Website

Schele, Linda and Miller, Mary Ellen. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York:George Brazillier Inc.

Sharer, Robert J. (1994). The Ancient Maya: Fifth Edition. Stanford:Stanford University Press

Scholars were able to read the Maya calender inscriptions before the rest of the ancient Maya glyphs because two of their calendars, the Tzolk'in and Haab', are still in use by traditional timekeepers in Mesoamerica, particularly in the Maya region (Rice 49). Also, the Tzolk'in and the Haab' calendars match the Aztecs' 260-day Tonalpohualli and 365-day Xiuhpohualli calendars in many ways. As the Aztecs are a particularly well-documented pre-Colombian culture, knowledge of their calendars helped early scholars make sense of the Maya ones (Rice 30-33).

The Tzolk'in Calendar

The 260-day Tzolk'in is the older calendar of the two and is thought to have existed from at least as early as 1600 BCE (Rice 33). It begins with a number from 1 to 13 attached to one of 20 named days in succession, each with its own glyph. The Tzolk'in's numerals and days can be combined to create 260 different variations before the same day and number combination are repeated in the cycle (Van Stone IV-6; Rice 31). Scholars are not precisely sure what the 260-day period correlates to, but theories include agricultural cycles, the gestation period of human pregnancy, and the movements of celestial bodies (particularly Venus). The mythically-charged Tzolk'in is generally referenced by its supporters for divinations of the supernatural (Rice 33-34; Van Stone IV-22).

The Haab' Calendar

The Haab' calendar is roughly equivalent to our own 365-day solar year. It operates similarly to the Tzolk'in, but instead of a 13 by 20 combination system (to make 260 days), it uses 18 by 20 to arrive at 360 days. Five extra days called wayeb' are tacked on at the end for a full 365 days. Something like months, the 18 periods of the Haab' are called winals, and each winal has 20 days (called k'in), which make a 360-day tun. The wayeb at the end of the year translate loosely as "dark" or "dangerous" (Van Stone IV-18). The earliest written evidence of the Haab' dates to the 6th century BCE in Oaxaca but it was likely in use long before that (Rice 45-46; Montgomery 2003:19). The Haab' correlates very closely to the approximately 365-day solar year but does not factor in an extra day every four years, a "leap year", as our Gregorian calendar does (ibid. 42). Most Maya dates are expressed as a combination of Tzolk'in and Haab'; the Aztec, in contrast, mainly used the Tzolk'in, and the Haab' appeared only rarely (Van Stone IV-20, 41).

The Tzolk'in and Haab' calendars interlock with each other like gears in a clock, in the interval known by Mayanists as the Calendar Round. During this round it takes a total of 37,960 days (52 years) before the same day names and numbers coincide in both calendars again (Rice 31). For the measurement of greater periods of time, however, there was a third Maya calendar. This calendar has no specific name that we are yet aware of, so Mayanist scholars have termed it the Long Count Calendar. Unlike the Calendar Round, which is still in use in some Maya communities, the Long Count Calendar fell out of use over 1000 years ago following the end of the Classic Period, and for the most part has only been readable by modern people for the past 80 years. This is thanks to the preeminent Mayanist Sir Eric Thompson, who cracked important parts of its glyphic code (Henderson 283, Van Stone IV-39).

The Long Count Calendar

The Long Count, like the 52-year Calendar Round, involves the interlocking cycles of the ever-repeating Tzolk'in and Haab', but it fixes them within a far longer range of time. This range is based upon an actual year with a set origin date - much like our Common Era (AD or CE) system currently tells us it has been 2009 years since the birth of Jesus Christ (Montgomery 2003:5). Long Count inscriptions start with what Mayanist scholars term the Initial Series Introducing Glyph (ISIG), a distinct, large glyph that tells us a date is about to be recorded (Montgomery 2003:5-6; Rice 172). This glyph is followed by other glyphs, each with a corresponding number to indicate the specific number of time units elapsed in each discrete category. These start at the top with the largest time units and go all the way down to the individual Calendar Round (Tzolk'in and Haab') dates, creating a system that measures over thousands of years right down to the specific day being recorded (Montgomery 2003:5).

Understanding the Long Count system is not easy, but there are some parallels that can be drawn to the Gregorian Calendar which can help. In our current system, the most common numeric expression of a date uses three units: day, month, year. Dates in our Gregorian Calendar format can be written in a number of ways, but for our purposes, we'll express November 12th, 2009 as 12.11.2009. The Maya had more than three units, and if one were so inclined, so too could we. If you wanted to add more time units to our system, the easiest thing to do is break the year 2009 into centuries and single years. This creates a date that looks like this: 12.11.09.20. Now, if we wanted to make something more similar to the Long Count, we would do it a little differently - we would reverse the order of the numbers, add a millennia unit and break apart the centuries and decades, then place the specific day and month at the end as they are the units that repeat periodically. So what we have looks like this: 2.0.0.9 November the 12th - Thursday. Functionally, this is much the same as the Long Count date 13.0.0.0.0 4 Ahau 3 K'ank'in, which equals the date December 21 (or 23), 2012 - but with some key differences.

The Maya Long Count has 5 units of time, each going up to 20 before adding a number to the bigger unit and flipping over to zero - this is in contrast to our system, in which numbers switch over after they hit 10 (i.e., 2.0.0.9 becomes 2.0.1.0). The five Maya Long Count units are named and organized as follows, starting from the right and going to the left: The k'in is a single day, which makes up the last digit in the series and goes up to 20. Positioned before the k'in is the winal count, each number of which equals 20 kins (a bit like short months). The winal is the only unit position that flips back to zero before it reaches 20, and in keeping with the divisible-by-20 format, the tun is made up of 18 winals or 360 k'in for a rough approximation of the solar year; this does not factor in the 5 "dark days" (wayeb') at the end of the year. Positioned before the tun is the k'atun, made up of 20 tuns, and positioned at the beginning of the series right after the ISIG is the b'aktun of 20 k'atuns - just short of 400 years (Montgomery 2003:40-43).

Written in our numerical system, a date from the Long Count would look something like this: 9.12.17.0.6, which would mean 9 b'aktuns, 12 k'atuns, 17 tuns, zero winals, and 6 k'ins, signifying the total amount of time that had passed since the fixed beginning date of the Long Count (ibid. 42). The earliest recorded complete Initial Series date yet found comes from the Gulf Coast Olmec culture site of Tres Zapotes, where a monument known as Stela C records an Initial Series date of 7.16.6.16.18 6 Etz'nab', which is equivalent to September 3rd (or 5th), 32 BCE (Rice 103). The earliest Long Count date from the central Maya lowlands (Peten region) is the date 8.12.14.8.15, found on Stela 29 at the city of Tikal and correlating to 292 CE (Henderson 116).

The current fixed point in time from which the Long Count Initial Series measures is a 4 Ajaw 8 Kumk'u day (Tzolk'in and Haab' dates, respectively) almost 13 b'aktuns ago, with the Long Count date being recorded as 13.0.0.0.0 - NOT 0.0.0.0.0 as would be expected; for whatever reason, the ancient Maya believed that the Long Count calendar reset itself at the end of a previous 13 b'aktun, 5125-year cycle rather than a 20 b'aktun 7885-year cycle (Rice 147; Van Stone FAQs). In our Gregorian calendar, this date corresponds to August 11th, 3114 BCE, though Mayanist scholars are split on whether to use a more recently-developed calendar correlation that sets the date two days later on August 13th (Rice 172; Van Stone IV-39; Montgomery 2003:43-44).

Either way, this date is well before the development of Maya civilization or its antecedents such as the Olmec, and is mythic in origin, probably based at least partially around numerology pertaining to the number 13 and perhaps agricultural associations with maize (corn) harvesting in August (Rice 176). Though the religious elites of different Classic Period Maya cities interpreted the calendars in different ways with widely-varying conclusions, this particular date held widespread significance as the creation point of the current world, while other dates referenced before this event stretch deeply back into time and earlier creations. In the case of Stela 1 in the city of Macanxoc, an event is recorded with a date stretching 13 periods earlier than 13.0.0.0.0, back to 13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.0.0.0.0 - a period of 41,943,040,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years (Montgomery 2003:80-84). In the ancient Maya worldview, there were many creations before our current world came into existence, but clearly they believed something significant was there in the distant past before the current agreed-upon origin point in 3114 BCE.

End of the World?

The Long Count date 13.0.0.0.0, falling on a 4 Ahau 3 K'ank'in Calendar Round date, will be replicated on December 21st (or 23rd), 2012. Maya epigraphers (experts on the glyphic inscriptions) have been aware of this upcoming date for decades. The limited records we have of ancient Maya k'atun endings (approximately 20 years) indicate that they would have celebrated this date with the construction of new monuments, a layer of fresh stucco and paint on existing buildings, veneration of ancestors, and public festivities and rituals (Rice 177-178, Sharer 546-547). Many people, particularly millenarianists and New Age spiritualists, believe that since the previous creation ended after 13 b'aktuns, the current creation will end at that point as well. The current glyphic evidence, however, provides little or no indication that the Maya believed anything will happen at the end of this particular 5125-year period (Van Stone III; Montgomery 2003:86; Houston 2008). Many experts in Maya studies believe, from written evidence at different sites, that the ancient Maya believed their Long Count calendar's b'aktun unit would simply reset (like a clock striking midnight), add a new upper-level time unit (a piktun of 13 b'akuns) and a new period of time will start, with life continuing on much as before following recognition of the period ending - but will the calendar actually reset after 13 b'aktuns this time?

There is substantial written evidence, from the ruins of major ceremonial centers, to indicate that the current b'aktun unit will not reset after it hits 13. Numerous dates in the future well after 2012 are frequently referenced in Classic Period Maya inscriptions, which almost always place emphasis on “impersonal temporal events that are safely predictable”; less action-oriented than purely calendrical (Houston and Stuart 1996:301). For example, 7th-century glyphs in the great Maya city of Palenque's Temple of the Inscriptions predict celebrations on the date 1.0.0.0.0.8 (over 4000 years into the future) surrounding the 80th Calendar Round anniversary of the coronation of Palenque's king Pakal Shield who is buried beneath the Temple. In this case, the Temple's carvers worked under the assumption that the b'aktuns would continue up past 13 to 20 (as 80 Calendar Rounds would have equalled up to an additional 6 b'aktuns), at which point it would flip to zero and a higher-order unit (a piktun) of 1 would be added to make for a total of 6 digits in the date (1.0.0.0.0.0) rather than our current 5 (which is 12.19.16.15.1 for the year 2009)(Van Stone II-85, Carrasco 2004). Thus, the carvers at Palenque believed the momentous period-ending was not set for the year 2012 but the year 4772; and the fact that they believed people after that point would be celebrating Pakal's reign indicates they had no reason to think there would any drastic break with the traditions of the past. Meanwhile, over at the Mesoamerican metropolis of Tikal, there is a monument bearing a date with the b'aktun position set to 19, 6 positions in the future beyond the upcoming 13.0.0.0.0 date and, again, indicating the calendar will not flip in 2012 as commonly believed (Van Stone II-97).

So...What DO the ancient Maya have to say about 2012 in their texts? Read on...

References:

Rice, Prudence M. (2007). Maya Calendar Origins: Monuments, Mythistory, and the Materialization of Time. Austin:University of Texas Press

Montgomery, John (2003). Cycles In Time: The Maya Calendar. Antigua (Guatemala):Editorial Laura Lee

Van Stone, Mark (2008). It's Not the End of the World: What the Ancient Maya Tell Us About 2012. Located online at the Foundation For The Advancement Of Mesoamerican Studies website.

Henderson, John (1997). The World of the Ancient Maya: Second Edition. Ithaca:Cornell University Press

Houston, Stephen (2008). What Will Not Happen In 2012. Online at Maya Decipherment epigraphy weblog.

Houston, Stephen and Stuart, David (1996). Of Gods, Glyphs, and Kings: Divinity and Rulership among the Classic Maya. Antiquity Magazine #70:289-312

Carrasco, Michael (2004). Unaahil B'aak: The Temples of Palenque (Temple of Inscriptions). Located online at the Wesleyan University Website

Schele, Linda and Miller, Mary Ellen. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York:George Brazillier Inc.

Sharer, Robert J. (1994). The Ancient Maya: Fifth Edition. Stanford:Stanford University Press

Donate $5 to CyArk

Help CyArk preserve more sites by making a small donation.

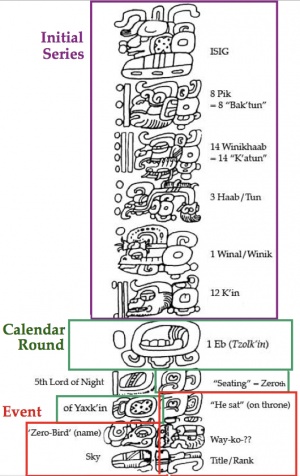

This example of a Maya Long Count date is carved on the back of a large piece of jade known as the <i>Leiden Plaque</i>. It describes the seating of a Maya Lord known as <i>Balam-Ahau-Chaan</i> on the date 8.14.3.1.12 1 <i>Eb</i> 0 <i>Yaxk'in</i>, equivalent to September 17th, 320 CE (AD) in our Gregorian calendar (<i>Photo by <a href="http://www.mayavase.com/">Justin Kerr</a></i>).

The writing on the Leiden Plaque is drawn here by Linda Schele and further illustrated/keynoted by Mark Van Stone, with the Initial Series glyphs boxed in purple, Calendar Round glyphs boxed in green, and the event commemorated boxed in red (<i>Van Stone IV:23; Schele and Miller 1986:Fig. 12</i>). Numbers attached to the glyphs are denoted by dots (equalling 1 each) and bars (equalling 5 each). Note the 3-arched ISIG glyph at the beginning and the standard 3-footed <i>cartouche</i> on the <i>Tzolk'in</i> date (<i>1 Eb</i>), as well as the lack of a number attached to the <i>Haab'</i> date (<i>0 Yaxk'in</i>). All these calendar and number systems are numerically designed around a <i>vigesimal</i> (20-based) system, in contrast to our own <i>decimal</i> (10-based) system; it is thought that this is because both the fingers and toes were counted in this tropical climate where closed-toe shoes were of little benefit (<i>Van Stone IV-6; Montgomery 2003:11; Rice 31</i>).

The Northern Acropolis of the city of Tikal, as seen from the staircase of the towering Temple II. The many royal burials located within the North Acropolis show a glimpse of the individual styles of Tikal as it formed in the Late Preclassic. While the major constructions such as step pyramids seem to have been built as tombs and monuments to powerful rulers, other constructions and monuments in the complex, including a great number of inscription-covered standing stone slabs known as <i>stelae</i> (seen here in front of the Northern Acropolis), commemorate <i>k'atun</i> endings and the public events that went along with them. In Tikal, the last known stela monument records a <i>k'atun</i> ending in 10.3.0.0.0 - corresponding to the year 889 in our calendar. This was, however, long after Tikal's power had waned and its earlier ruling dynasties had vanished (<i>Sharer 271</i>). Photo by <a href="http://archive.cyark.org/tikal-intro">CyArk</a>.